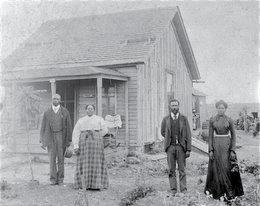

Early Nicodemus settlers. (Photo from private collection of Irwin and Minerva W. Sayers)

Charette conducted at Spitzer School of Architecture prior to field trip to Nicodemus, Kan.

Spitzer School Proposal Positions Role of Parks in Context of 21st Century Diversity

“Finding Common Ground,” a plan for the Nicodemus National Historic Site in Nicodemus, Kan., produced by a studio of first-year graduate landscape architecture students in The City College of New York’s Bernard and Anne Spitzer School of Architecture, received one of two awards of excellence in “Parks for the People,” a student competition to reimagine America’s National Parks.

The CCNY team and a team from Rutgers University received top honors in the contest, which was sponsored by the National Park Service, Van Alen Institute and the National Parks Conservation Association. The winning teams, announced September 19 in Washington, were selected from nine finalist teams that conducted studios for one of seven national park sites. Forty-one schools participated in the initial round.

“Our aim for Nicodemus was to position it within a new order of national parks that reflect the diversity of 21st century America,” said Denise Hoffman-Brandt, director of the Spitzer School’s landscape architecture program, who instructed the studio with the assistance of Andrew Zientek. “By considering Nicodemus as a paradigm shift in park planning and design, we sought to provoke a new vision for the site and the National Park Service as a whole.”

Students in the studio were: Sam Berkheiser, Kathleen Cholewka, Nicole Diz, Lindsay Foehrenbach, Lara Gelband, Kristen Henry, Elizabeth Luzzi, Sara Malmqvist, Blake Morrison, Ryan Morrison, Grace Ng, Peter Pavicevik, Jin Sha, Stephanie Skrobach, Adam Thyberg, Liza Trafton and Danny Turgeon.

In a remote area of the Kansas prairie, the Nicodemus National Historic Site tells the story of an African-American community settled in the late 1870s by migrants from Kentucky. One of the oldest continuously occupied black townships west of the Mississippi River, Nicodemus commemorates “a continuum of history” rather than a single era or event. Because of its location and limited awareness, it draws few visitors.

The site includes a preserved school and church, a NPS visitor’s center in the old town hall and several privately owned residences. From a peak of around 3,000, the year-round population has dwindled to seven. However, many descendants and extended families of the original families return each year for Homecoming and stay in homes still in their possession.

Prior to traveling to the site in February, the landscape architecture program co-hosted a charrette for the project with the Spitzer School’s J. Max Bond Center on Design for the Just City. Several Spitzer School faculty members contributed to the studio, including Professors Isaac Gertman, Toni Griffin, Marta Gutman, Catherine Seavitt, Michael Sorkin and Elisabetta Terragni.

Out of this came an approach for the studio: Rather than interpret Nicodemus’ past and present, NPS would provide a framework for the narratives of people of Nicodemus, past, present and future. “Where there is a living community with the capacity to tell their story, NPS must reframe their mission to reveal America’s narrative, and instead see their role as creating an armature for those communities to tell their own story,” the studio proposal states.

Because the Nicodemus site encompasses a still-occupied community, two principles drove the design process: 1. In order to celebrate black land ownership, there would be no incursion onto private land; 2. The design would have to serve multiple stakeholders including local residents, property-owners and Homecoming participants, and tourists visiting the NPS site.

The proposal called on NPS to operate solely within the public area of the plat, i.e. the mapped out areas of the community. To delineate the plat, students in the studio demarcated the original town plat and showed where visitor services and interpretive features would be located along the town’s public highways. The proposal calls for significant locations to be identified with roadside markers.

In addition, they recommended returning the visitor center to civic use so that residents and property owners could hold meetings and other events there. They also proposed setting aside space in the building for the Nicodemus Historical Society. Usufruct agreements, allowing public access to private property, were proposed to stabilize damaged and declining structures on the site and enliven the domestic landscape to reflect that Nicodemus is a living community.

The physical site design proposal called for the creation of three trails: a 30-mile trail commemorating the route taken by settlers from the railroad station in Ellis; a town trail connecting historic locations, and a “Last Mile” trail from the town center to the cemetery. The trails and site plans tailored to the town's different user groups deepen its social, cultural, and environmental contexts.

Because Nicodemus draws significance within the context of the larger stories of westward migration and African-American history, the studio created a research tool called the Nicodemus web, to build new connections and partnerships for the site. “Nicodemus needs to build relationships with historical communities and black communities and we have methods now to help it access these sites,” Professor Hoffman-Brandt said. “It is very likely, and not undesirable that more people will visit Nicodemus, Kan., online than in person.”

Jurors praised the studio for producing a “deeply engaged and sophisticated analysis, revealing Nicodemus and its park experience as a multi-scalar phenomenon. This expanded vision of the 21st century park is grounded in the idea that American cities were built upon mobility networks. The proposal shows that Nicodemus was not an isolated experience, but a hub in a network tied to people seeking social and economic freedom.”

MEDIA CONTACT

Ellis Simon

p: 212.650.6460

e:

esimon@ccny.cuny.edu