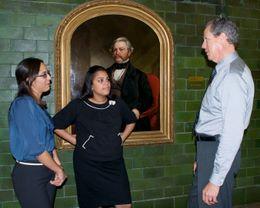

Dr. Darwin Deen, MD, (right) medical professor in the Sophie Davis School of Biomedical Education and fifth-year medical students Maryann Garcia (left) and Joanna Fernandez are studying whether patient activation interventions can help patients prepare questions for their doctors that can lead to better healthcare outcomes.

Patient Activation Interventions Help Raise Awareness for Role in Managing Health, Could Yield Better Outcomes

For some patients, knowing how to ask questions in a doctor’s office could make a huge difference in their outcomes. A pilot program at The City College of New York’s Sophie Davis School of Biomedical Education is teaching future physicians to help patients take charge of their health by querying their medical providers.

“Some patients are good at effectively negotiating the healthcare system. They know what they want and how to partner with their doctor so they can take charge of their health,” says Dr. Darwin Deen, MD, a medical professor in Sophie Davis’ Department of Community Health and Social Medicine.

“Others don’t have that perspective. They come in and expect the doctor to solve their problem. Data show those who don’t take responsibility tend not to have good outcomes.”

As a medical student, Professor Deen was trained to become a consultant who could help people solve problems. However, interfacing with patients who could not ask questions posed challenges to that process.

Sophie Davis faculty and students have conducted research on health literacy and patient activation. However, the two concepts are not the same, he points out. “Knowledge doesn’t produce behavior.”

His search for ways to change behavior led him to the Dan Rothstein and Luz Santana with the Right Question Institute, a Cambridge, Mass.-based non-profit educational organization that helps people in low and moderate-income communities learn to advocate for themselves. Through its healthcare curriculum, patients learn to take greater ownership of their own health care and partner more effectively with their healthcare providers.

Two years ago Professor Deen and Dr. Marthe Gold, MD, the department chair, conducted a test program at Sophie Davis with a curriculum adapted from the Right Question model. Last year, it was adapted as part of the school’s standard curriculum; members of the Class of 2012 are the first cohort required to learn the strategy as part of a course that Professor Deen teaches from November through May.

The students are trained to conduct patient activation interventions, which are 10-minute conversations before the patient enters the examination room. They are intended to help the patient understand his or her role in their health and to generate questions for the visit.

“We want patients to be able to ask the right questions – those questions that will give them the information they need to contribute to managing their diseases,” Professor Deen explains. “They need to prioritize, so we recommend that they come up with eight to 10 questions, but prioritize their top three to ask.”

Patients must understand that what they do between visits will play a bigger role in their health outcome than what the doctor does, he adds. “It’s not a question of how good the doctor or the medicine is.”

In addition to lectures and small group meetings, Professor Deen employs role modeling and videotaping to give students practice and provide feedback. The course also teaches students how to talk to patients and how to take a medical history.

“Teaching this is challenging,” he says. “We’re teaching them how patients think and feel in their interactions with physicians at the same time that they are learning the doctor’s perspective. It can be frustrating for them since they are in the early stages of learning medicine and their knowledge of specific diseases is limited.”

.

Along with some of his students, Professor Deen is in the early stages of research to measure the efficacy of the patient activation intervention. “We want to know what goes on in the doctor’s office in order to see whether the interventions seem coercive, whether patients behave differently and how doctors feel about it,” he explains. “The latter is a major concern since doctors don’t have enough time and we want them to respond positively to patients’ questions.”

Preliminary findings suggest that the number of questions patients ask does not bother physicians. “People think doctors don’t have time for too many questions, but the reality is the number of questions doesn’t seem to influence doctors’ perspective,” says Maryann Garcia, a fifth-year Sophie Davis student who spent last summer as a research assistant with Professor Deen.

Ms. Garcia sat in on 120 patient/provider encounters at two clinics in Manhattan and the Bronx and recorded patient questions. Then, she debriefed doctors on their patients’ question-asking behavior to see whether the number of questions affected the provider’s perspective on how engaged they thought the patient was and whether they asked too many or too few questions.

The findings were statistically significant but not clinically significant, she notes. Factors that impact the patient-doctor relationship, such as type of visit, previous relationship with patient and length of the relationship, were not accounted for. “The type of question a patient who has been with the same doctor for 10 years asks may not be the same as that posed by a new patient,” says Ms. Garcia, who will serve as a teaching assistant for this year’s class.

“People have difficulty controlling their health, but asking questions is a way to take control,” says Joanna Fernandez, a classmate of Ms. Garcia who shared the patient activation intervention as a Mayor’s Health Literacy Fellow in 2010. “Patients felt it gave them a sense of empowerment.” However, people with limited education and English language skills may be too embarrassed to ask questions, she notes, adding that this problem was common among older and immigrant populations.

Ms. Garcia concurs, “Patient activation is not a magic bullet.” While asking questions is the ideal form of communication, some patients seek information by making statements, she notes.

“As a future physician, it’s training me to be better at asking questions and helping me highlight to patients the importance of them asking me to do something, she says. “If they don’t ask, they will leave unhappy with their questions unanswered.

“The goal is to change behavior for future visits,” concludes Professor Deen. “Changing the way patients interact with doctors is the brass ring for us.”

On the Internet

Sophie Davis School of Biomedical Education

Professor Deen’s web page

Right Question Institute

MEDIA CONTACT

Ellis Simon

p: 212.650.6460

e:

esimon@ccny.cuny.edu