Adriana Espinosa, Ph.D.

Dr. Adriana Espinosa, the scholar-in-residence at the MPA Program, outlines numerous studies showing how gender bias and racial bias influence hiring, promotion, and the psychological environment of the workplace - and what this means for aspiring public managers.

A diverse workplace fosters innovation, improves performance, and heightens creativity.

According to the National Academy of Sciences, a diverse workforce is vital for ensuring that organizations and nations remain globally competitive.

Nonetheless, women as well as Black and Hispanic individuals remain severely underrepresented in leadership positions and in the Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) professions.

These jobs drive the global economy and are among the most lucrative careers.

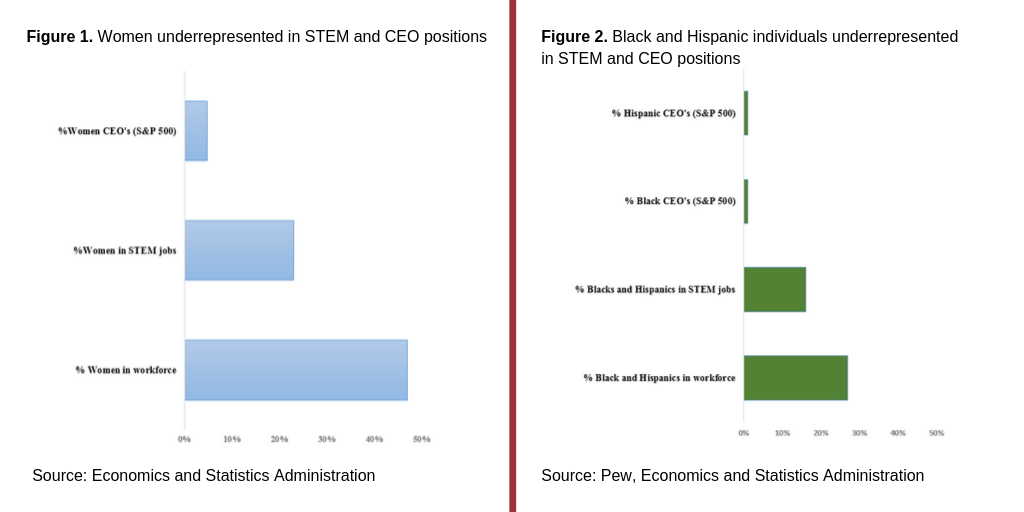

Although women make up approximately half of the US working population, women hold less than a quarter of STEM occupations and a much lower fraction of executive positions (see Figure 1).

Similarly, Black and Hispanic individuals constitute approximately 27% of the working population, but they represent less than one fifth of STEM jobs, and less than 3% of leadership positions (see Figure 2).

Not surprisingly, among Black and Hispanic persons, males outnumber women in both CEO positions and STEM careers.

Explicit Bias: A Hostile Workplace

Numerous studies show that explicit forms of differential treatment contribute significantly to the underrepresentation of women and racial and ethnic minorities.

The most explicit forms involve sexual harassment, unfair pay, and bias in the allocation of promotions and work assignments.

Surveys conducted by the Pew Research Center and the American Association of University Women indicate that the majority of women in STEM jobs report that they have experienced gender-based discrimination at work, compared to one fifth of men in STEM jobs.

Implicit Bias in Letters of Recommendation

Differential treatment can also take less overt forms and reflect negative stereotypes based on gender, race, or ethnicity.

A common form is the use of undermining language by peers or supervisors, males and females alike, to refer to women’s qualifications or to credit their work.

Multiple studies show that the language used to describe a candidate’s qualifications in letters of recommendation vary by the sex of the applicant.

Women are often described with communal language such as ‘nice’ or ‘friendly’ and with words that cast doubt, such as ‘might’ and ‘could’. Men, on the other hand, are often described with agentic language, such as ‘leader’, ‘competent’, and ‘outstanding’.

Letters of recommendation are fundamental for hiring and promotion, so such invalidation of women’s qualifications relative to males’ has a negative impact on women’s career trajectories.

Implicit Bias in Resume Selection

Implicit bias also affects whether a racial or ethnic minority candidate gets called back for an interview.

A well-known social experiment revealed that candidates with African-American-sounding names were 50% less likely to get an invitation for an interview than equally qualified candidates with White-sounding names.

Aware of the potential biases of hiring managers, applicants may engage in what is known as resume whitening, whereby minority individuals mask any ethnic indicators prior to applying for a job.

Evidence shows that resume whitening yields higher callback rates, but little is known about whether the applicants are more likely to be hired and about how resume whitening affects the applicant’s self-esteem.

Stereotype Threat

A great deal of experimental evidence has emphasized the harmful impact of negative stereotypes on the mental health, performance, and success of women and ethnic and racial minorities.

The evidence shows that words or actions that promote negative gender stereotypes about individuals’ capacity to do math or to lead, for example, can become self-fulfilling because of the stress they cause for the stereotyped individual.

These harmful words or actions often occur in the form of microaggressions, which are frequent and common slights towards a particular minority group. Multiple studies document that microaggressions not only impair the job opportunities of those exposed to them, but also severely affect the individual’s mental and physical state, leading to depression, suicidal thoughts, and heart-related conditions.

Need Broader Scope of Diversity

Diversity includes a broad range of observable and non-observable domains, yet the vast literature on workplace diversity, accumulated from decades of research, focuses mainly on sex and ethnicity, and many ethnicities are omitted.

Focusing too narrowly on women, Black and Hispanic individuals undermines the importance of difference in other areas. The explicit and implicit barriers that affect the representation of women, Black and Hispanic individuals in leadership positions and STEM professions are likely to affect many other groups, as well.

It is imperative that research on workplace diversity broaden its scope to include more dimensions of diversity.

What Can Public Managers Do to Avoid Perpetuating Bias?

It is crucial for MPA students to study the way both explicit and implicit bias affect workplace diversity.

Here are some tips on how to avoid perpetuating bias in the workplace:

- Recognize your biases. This can include the use of external sources that currently exist to identify one’s implicit biases. The most common measure is the Implicit Association Test (IAT) by Project Implicit in Harvard University.

- Be aware of your language, whether verbal or written. Use Gender Bias Calculators if necessary.

- Recognize that equal treatment does not imply equity, as some opportunities that are presumably offered to everyone are unattainable for some individuals (e.g., single mothers cannot likely attend a professional development workshop scheduled at 4 PM).

- Recognize that diversity is a very broad term that corresponds to inclusiveness.

- Do not be silent just because the situation does not involve you.

Being aware of the persistence of these forms of bias can help MPA students reflect on their own potential biases, better cope with others’ biases toward them, and ultimately create more accessible, inclusive, and diverse workplaces.

Dr. Adriana Espinosa is an assistant professor in the Department of Psychology at the Colin Powell School for Civic and Global Leadership.

Want to become part of the MPA Program? Find out more about our internship program, scholarships, and career development.

References

Aronson, J., & Inzlicht, M. (2004). The ups and downs of attributional ambiguity: Stereotype vulnerability and the academic self-knowledge of African-American students. Psychological Science, 15, 829-836.

Aronson, J. , Fried, C., & Good, C. (2002). Reducing the effects of stereotype threat on African American college students by shaping theories of intelligence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 38, 113-125.

Bertrand, M., & Mullainathan, S. (2003). Are Emily and Greg more employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A field experiment on labor market discrimination. NBER Working Paper Series, No. 9873. Retrieved from NBER.

Funk, C. & Parker, K. (January 9, 2018). Women and Men in STEM Often at Odds Over Workplace Equity. Pew Research Center Social and Demographic Trends. Retrieved from Pew Social Trends.

Garrison, H. (2013). Underrepresentation by race-ethnicity across stages of U.S. science and engineering education. CBE Life Science Education, 12(3), 357-363.

Hill, C., Corbett, C., & St. Rose, A. (2010). Why So Few? Women in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics. American Association of University Women. Retrieved from AAUW.

Kang, S. K., DeCelles, K. A., Tilcsik, A., & June, S. (2016). Whitened resumes: Race and self-presentation in the labor market. Administrative Science Quarterly, 61(3), 469-502.

Madera, J. M., Hebl, M. R., Dial, H., Martin, R., & Valian, V. (2018). Raising doubt in letters of recommendation for academia: Gender differences and their impact. Journal of Business and Psychology. doi: 10.1007/s10869-018-9541-1

Madera, J. M., Hebl, M. R., & Martin, R. C. (2009). Gender and letters of recommendation for academia: Agentic and communal differences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(6), 1591-1599.

Nadal, K.L., Griffin, K.E., Wong, Y., Hamit, S. & Rasmus, M. (2014). The Impact of Racial Microaggressions on Mental Health: Counseling Implications for Clients of Color. Journal of Counseling & Development. Vol. 9. Retrieved from Academia.edu.

O'Keefe, V.M., Wingate, L.R., Cole, A.B., Hollingsworth, D.W., Tucker, R.P. (2015). Seemingly Harmless Racial Communications Are Not So Harmless: Racial Microaggressions Lead to Suicidal Ideation by Way of Depression Symptoms. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. Vol. 45, Iss. 5. Retrieved from Wiley.

Spencer, S. J., Steele, C. M., & Quinn, D. M. (1999). Stereotype threat and women's math performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 35, 4-28.

Torres L. & Taknint J.T. (2015). Ethnic microaggressions, traumatic stress symptoms, and Latino depression: A moderated mediational model. Journal of Counseling Psychology. Jul; 62(3):393-401. Retrieved from NCBI.

U.S. Department of Commerce / Economics and Statistics Administration. (2011). Women in STEM: A Gender Gap to Innovation (ESA Issue Brief #04-11). Retrieved on October 7, 2018 via Commerce.gov.

Walls, M.L., Gonzalez, J., Gladney, T., & Onello, E. (2015). Unconscious Biases: Racial Microaggressions in American Indian Health Care. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. Mar-Apr; 28(2): 231–239. Retrieved from NCBI.