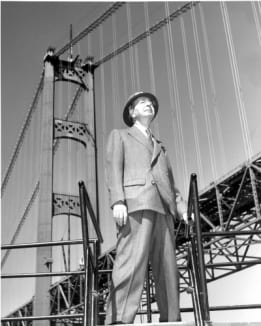

Bridge Builder Extraordinaire Founder of the American Association of Engineers

“A bridge is a poem stretched across a river, a symphony of stone and steel.”

David Steinman

During his stellar career, New York native David Barnard Steinman and his associates were responsible for the design and construction of more than 400 bridges, including the Henry Hudson Bridge in New York, the Mackinac Bridge in Michigan, the Deer Isle Bridge in Mane, and the St. Johns Bridge in Oregon. And for 40 years he was the leading proponent of long-span suspension bridges, rivaled only by the Swiss-born Othmar Ammann.

Steinman was born in 1886 in the shadow of the Brooklyn Bridge; little is known of his parents and six siblings other than the fact that Steinman failed to mention them later in his life. A mathematical prodigy, Steinman worked his way through City College, graduating summa cum laude in 1906. Immediately thereafter, he attended Columbia University and completed three degrees, culminating with a doctorate in civil engineering. Steinman’s PhD thesis, “The Design of the Henry Hudson Memorial Bridge as a Steel Arch,” would become a reality 25 years later.

Steinman accepted a teaching position at the University of Idaho, but soon longed for New York. He contacted Gustav Lindenthal about the possibility of working with him on the Hell’s Gate Bridge, and became Lindenthal’s special assistant, second only to another young bridge builder, Othmar Ammann. Thus began the rivalry between Steinman and Ammann that lasted for four decades. In 1920 Steinman teamed up with Holton Robinson, engineer of the Williamsburg Bridge, and the two form

ed a company that would design and construct hundreds of bridges until Robinson’s death in 1945, including the Florianopolis Bridge, the largest span bridge in South America, and the Carquinez Strait Bridge northeast of San Francisco. It was during this period that Steinman, as president of the American Association of Engineers, began campaigning for more stringent educational and ethical standards within the engineering profession. His concern for professionalism continued with he founded the National Society of Professional Engineers in 1934 and served and the society’s first president.

By then Steinman had established himself as one of the premier bridge builders of his generation, but his creations were eclipsed by Ammann’s George Washington Bridge in 1931, and Joseph Strauss’ Golden Gate Bridge in 1937. Steinman made plans to seize the span record by building the “Liberty Bridge” across New York Harbor, but with the collapse of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge in 1940 the future of long-span suspension bridges appeared in jeopardy. The disaster prompted him to publish a series of articles on the aerodynamic stability of bridge design. This theoretical groundwork led to the Mackinac Bridge project connecting the Upper and Lower Peninsulas of Michigan – perhaps his greatest triumph.

Steinman’s design innovations, such as open-grid roadways and stiffened trusses, raised the theoretical critical wind velocity of the new design to 642 miles per hour. Though the Colden Gate retained the record for the longest suspended span between towers, the Mackinac Bridge was actually longer in total suspended span by almost 1,000 feet. When the highly sought after contract for the Verrazano Bridge spanning New York Harbor went to his old rival Ammann because of his political ties to Robert Moses, Steinman prepared plans to cross the two-mile wide Strait of Messina between Sicily and the Italian mainland, but the Messina Bridge remained on the drawing board at his death.

Shortly after Steinman’s death in 1960, CCNY’s engineering faculty unanimously recommended – and President Buell Gallagher and the Board of Education approved – that the new School of Technology opening that same year be named the David B. Steinman Hall in honor of this early alumnus’ outstanding achievements.

Last Updated: 04/30/2019 13:35